The Shift in Chain Design: From General-Purpose to Application-Specific

The “Game Console” analogy

For anyone who knows me and my past work, over the past two years, I have been researching and speaking about Polkadot at conferences in SEA. For the reader’s context, Polkadot is well-known for its rollup-as-a-service (RaaS) infrastructure, which enables anyone to easily launch a new rollup and customize the runtime logic.

And one of the analogies I love the most and use nearly every time I talk about rollups is the game cartridge analogy. Imagine rollup hub technology is like the game console, while the game cartridge is the rollup, which has its own storage space with different kinds of logic coded in the ROM card (except that execution is sharded and handled on the rollup, not on the base layer in this analogy).

This design is applied to most of the RaaS infrastructure that you can find in the industry at the time this article is written: Polkadot, Optimism, ZK Sync, or Arbitrum Orbit. They differ slightly in some components, but the overall idea remains the same. In the early days of modular blockchain design, the appchain paradigm promised sovereignty. Every project could own its own blockspace, customize its economics, and scale independently.

“Blockspace is the commodity that powers the heartbeats of all cryptocurrency networks.” - Ethereum Blockspace - Who Gets What and Why, Paradigm

General-purpose network is not a one-size-fits-all

However, the cost of independence soon became apparent — liquidity isolation. As liquidity splintered across dozens of sovereign chains, capital efficiency collapsed. Bridges emerged to patch fragmentation, but they only reintroduced the one thing crypto was supposed to eliminate: trust in intermediaries.

Today, the paradigm is shifting again.

As RaaS technologies involve, launching a new chain is much easier compared to the early stage of layer 2. Application-specific chains will be more demanding, as they solve certain problems that are hard to solve if you share the blockspace with other applications.

We will dive into more use cases in future articles, but today, we will talk about liquidity chains where the exchange becomes the chain, and the chain becomes the matching engine.

This is the philosophy behind new architectures like HyperLiquid or Lighter — systems that no longer treat trading as an application, but as a first-class consensus process.

From Application to Consensus: When Trading Becomes the Chain

When we think about traditional blockchains, we imagine applications built on top of consensus - protocols that submit transactions to a shared state machine. The blockchain sequences, validates, and settles those transactions, but it doesn’t understand their economic meaning.

For general-purpose compute, that abstraction works beautifully.

For trading systems, it breaks.

A trading engine is fundamentally a temporal consensus mechanism — it coordinates not what trades happen, but when they happen and in what order.

That sequencing defines price, fairness, and ultimately liquidity itself.

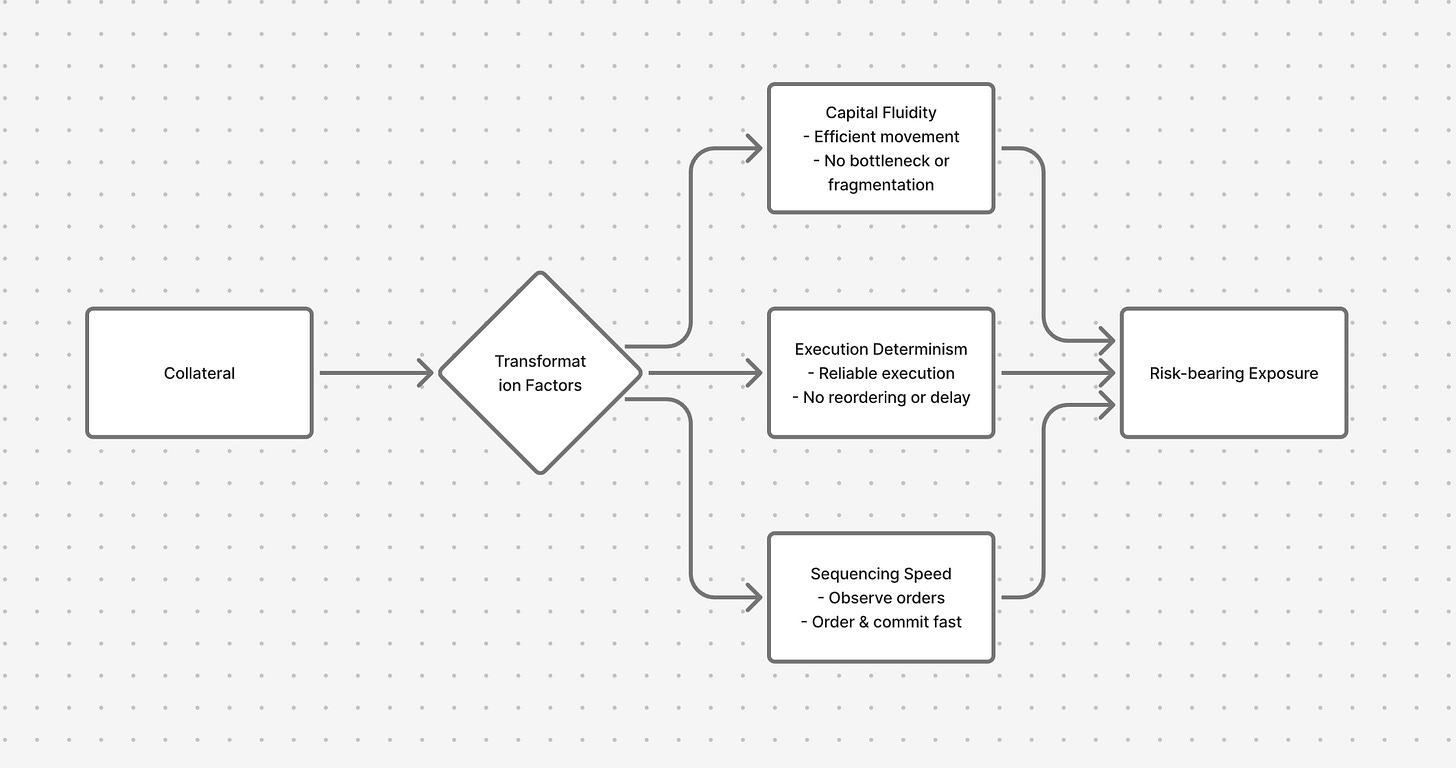

At its essence, liquidity measures the rate at which collateral transforms into risk-bearing exposure. That transformation depends on three tightly-coupled factors:

Sequencing speed — how fast orders can be observed, ordered, and committed.

Execution determinism — how reliably those orders execute (no unexpected delays, reordering, variable latency).

Capital fluidity — how efficiently capital moves across exposures without bottleneck, fragmentation, or delay.

Most general-purpose blockchains (and even many optimized L2s) are built with goals like throughput (TPS) or cost efficiency (low fees) in mind — but not temporal precision (low and predictable latency, highly deterministic ordering). That trade-off is acceptable for general computation, where a delay of a few hundred milliseconds or even seconds may not be significant.

But markets are fundamentally temporal machines — systems where time itself becomes a dimension of risk and value. In a high-frequency context, a 200-millisecond delay in order inclusion or in when that order becomes final can reprice the entire book, shift market state, or provide an edge to someone with faster access.

Why general-purpose chains fall short

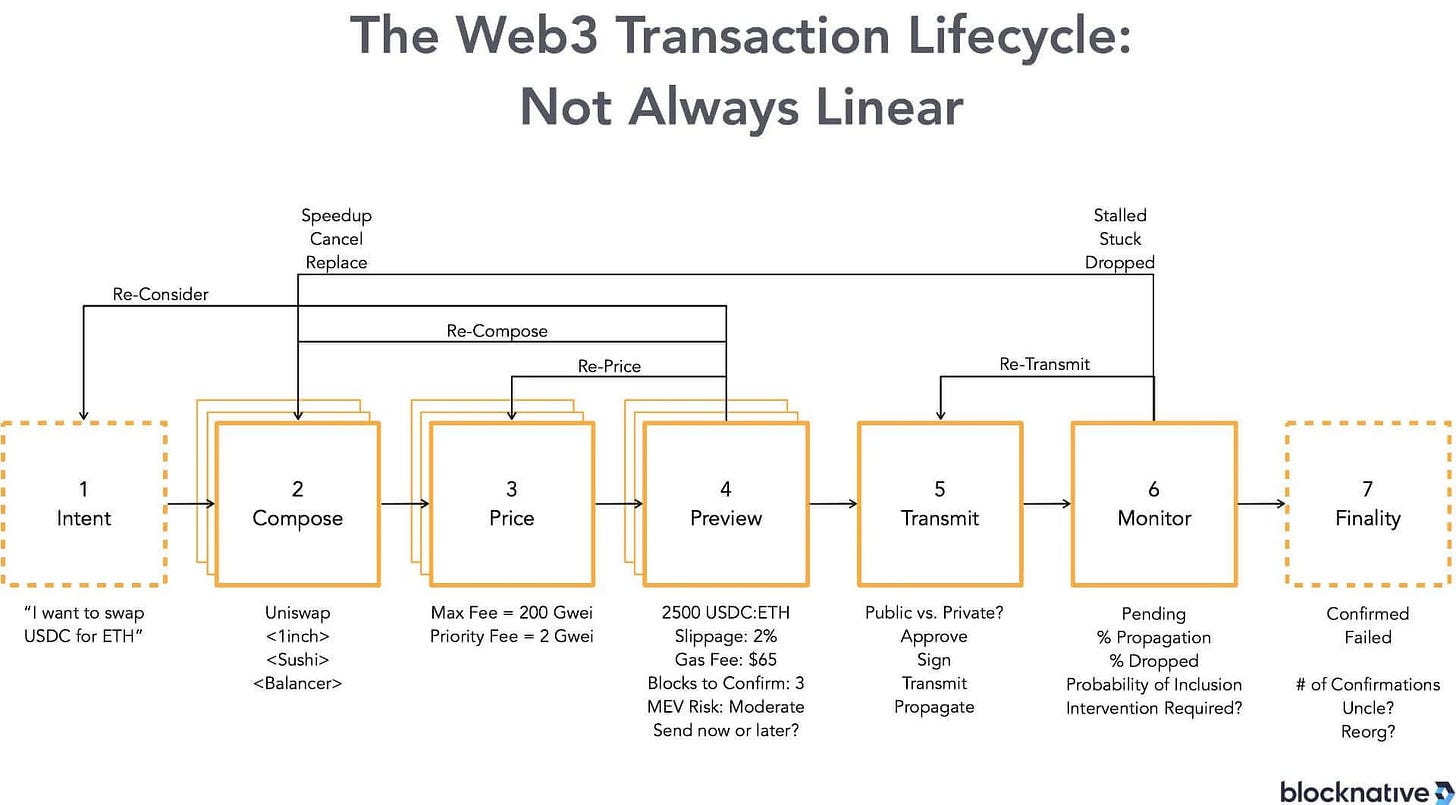

Many chains rely on mempools, asynchronous order propagation, dynamic block inclusion, and probabilistic finality. That means the timing from user-submission to final settlement is variable.

When you cannot predict when your order will appear (and when it becomes irreversible), you introduce temporal variance per trade. That variance raises uncertainty, widens required spreads, degrades liquidity depth.

For a liquidity-focused environment (especially for high-frequency trading, perpetuals, tight spreads), what matters is notand just raw TPS, but how predictable and tight the latency and order-sequencing bounds are.

The consensus mechanism in a generic blockchain solves “state agreement” (what the ledger looks like after some block) but not necessarily “time agreement” (when exactly the trade hit, in what order relative to others, with negligible jitter). That gap is critical when milliseconds matter.

The liquidity-chain paradigm

In a chain designed for liquidity (e.g., a hypothetical or actual architecture like HyperLiquid), the objective is inverted: instead of maximizing TPS, you aim to minimize variance per trade. You aim for temporal determinism + tight latency bounds + capital fluidity.

In this paradigm:

Consensus is not just “what block” but “when in that block” and “in what sequence relative to all peers”.

The network is optimized for predictable latency, deterministic matching/sequencing, and deep shared liquidity pools that any participant can tap into quickly.

Orders, cancellations, trades, liquidations — all operate in a regime where timing uncertainty is very low, removal of arbitrary delay or mempool racing, and capital can shift between exposures with minimal friction.

When participants share a deterministic view of time, the “uncertainty premium” — the extra spread or cost required to protect against latency/ordering risk — shrinks. That means tighter spreads, deeper liquidity, and more efficient use of collateral.

The metric of interest becomes variance per trade (or “latency-uncertainty per trade”) rather than simply “transactions per second”. A chain delivering 200,000 trades per second but with large temporal jitter is worse for a liquidity machine than one delivering 50,000 trades per second with sub-10-millisecond determinism. (”In-depth analysis of the HyperLiquid Project” - Chain Catcher)

To compare it more easily, let’s take Uniswap and HyperLiquid into comparison. The determinism in the transaction status of Uniswap relies on the chain on which its smart contract is deployed. For example, if it is on Ethereum, the settlement depends on the network status of Ethereum and fees taken to follow the gas mechanism.

As an application built on top of Ethereum, there are a lot of externalities you need to consider and optimize, especially for the onchain orderbook.

CLOB = Central Limit Order Book. There is a detailed explanation that you can read more here

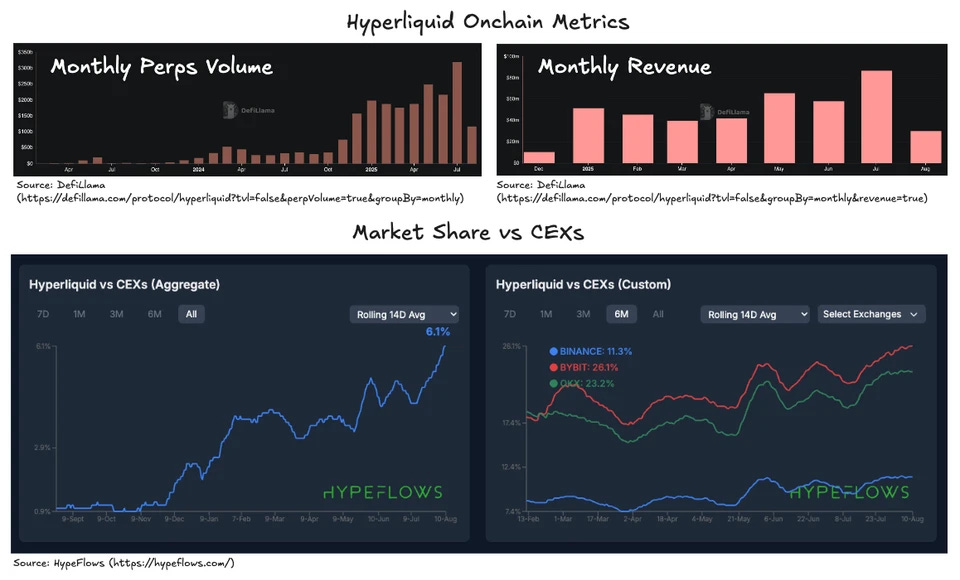

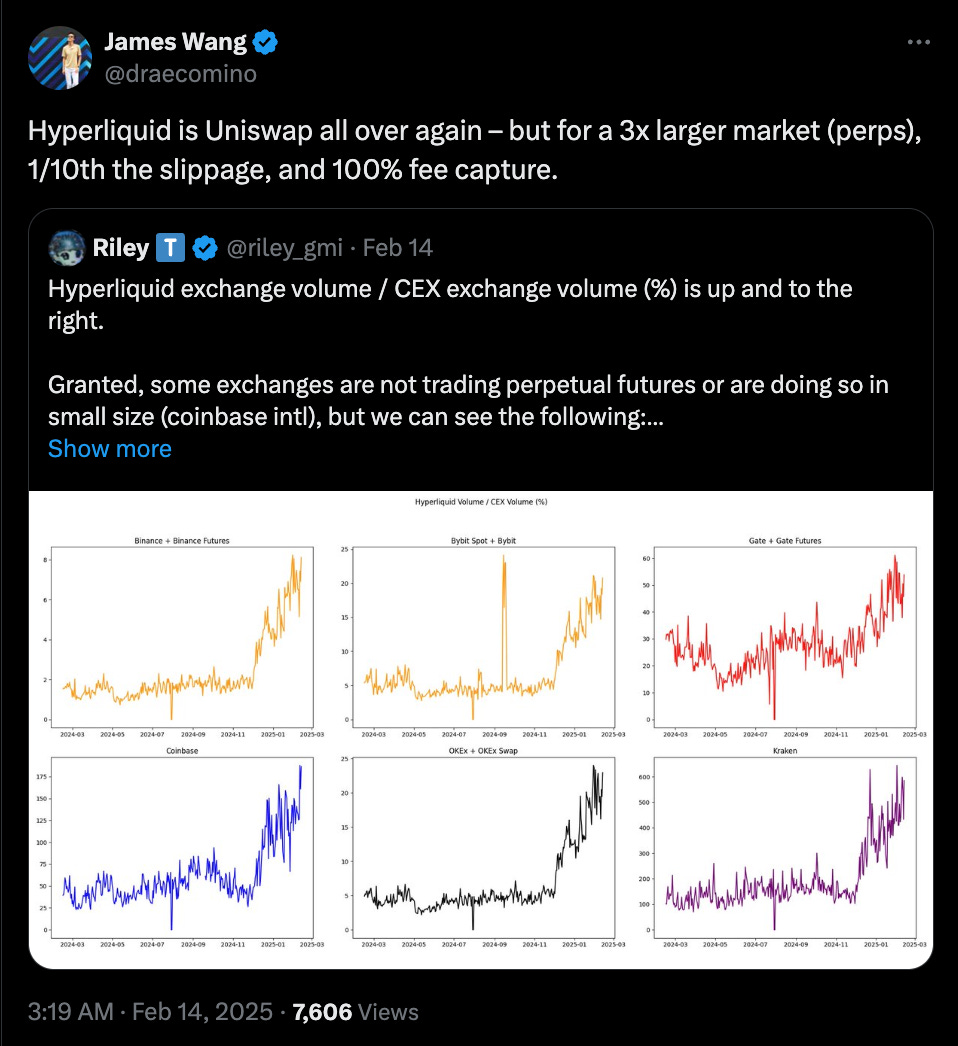

HyperLiquid has proved its position in the current market as one of the fastest-growing chains in trading volume since its launch and created a brand new narrative around the liquidity chain. Let’s dive into how HyperLiquid is designed to support the high-demand trading use cases.

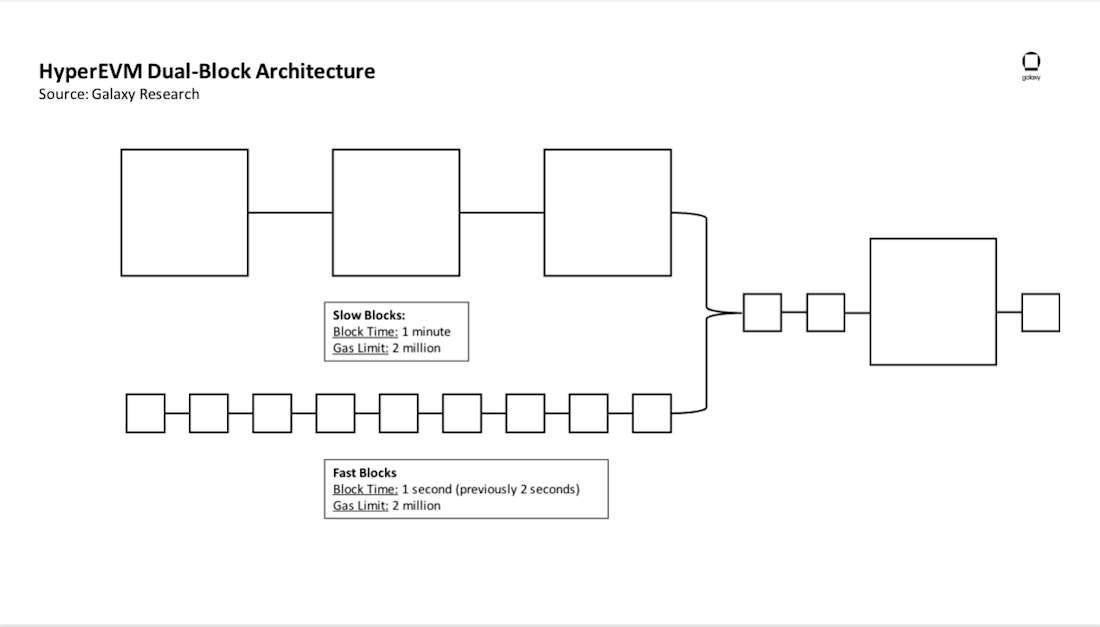

HyperLiquid’s architecture is uniquely optimized for high-frequency trading through two core innovations — the HyperEVM and its dual block mechanism — both designed to ensure that every block directly serves the central limit order book (CLOB).

At its foundation, the HyperEVM extends the familiar EVM model while removing its general-purpose constraints. Instead of handling arbitrary smart contract logic, HyperEVM is tuned for deterministic, low-latency order processing, integrating the matching engine directly into the execution layer. This means that every on-chain operation — from order placement to cancellation — executes as a native primitive rather than an interpreted contract call, minimizing gas overhead and execution delay.

The dual block mechanism further refines how blockspace is allocated. HyperLiquid separates block production into two synchronized layers:

Consensus blocks, which finalize and order transactions for state consistency.

Execution blocks, which handle high-frequency order flow and trade matching in parallel.

This separation allows the chain to process trades continuously without waiting for full consensus cycles, effectively decoupling latency-sensitive execution from finality. As a result, the network achieves both sub-second responsiveness for traders and robust settlement guarantees for the underlying ledger.

Together, HyperEVM and the dual block mechanism transform blockspace into specialized market bandwidth — a vertically optimized environment where every computation contributes to liquidity, matching efficiency, and capital throughput, rather than competing for gas or generalized compute.

HyperLiquid provides a super detailed documentation to explain their architecture, which you can find here: About Hyperliquid

In essence, the liquidity chain is the future of financial-grade blockspace. It proves that for applications where milliseconds translate to billions in value, blockspace must be designed around the specific physics of that application—be it trading, gaming, or high-throughput data processing—rather than treating it as a general-purpose utility. The appchain model isn’t dead; it’s just getting its specialization down to a science.

Written by Tin Chung